It can be a simple statement about retaining the copyrights to your artwork. This section doesn’t have to be extensive. They are written to specify details about work to be undertaken and the expected outcomes.This paper has been commissioned by Public Art South West from Henry Lydiate, a barrister who has specialised in the law relating to the visual arts since he founded Artlaw Services in 1978, and in response to the many requests received for guidance in relation to public art commissions and the legal and practical issues involved in their successful execution and management.Artist’s Right. In this Contract, the Artist agrees to indemnify the Client (and its affiliates and its and their directors, officers, employees, and agents) from and against all liabilities, losses, damages, and expenses (including reasonable attorneys’ fees) related to a third-party claim or proceeding arising out of: (i) the work the Artist has done under this Contract (ii) a breach by the Artist of its obligations under this The agreement or contract is the legal document between an artist or owner of an artwork and a borrowing institution, or between an exhibition organizer and the host venue.

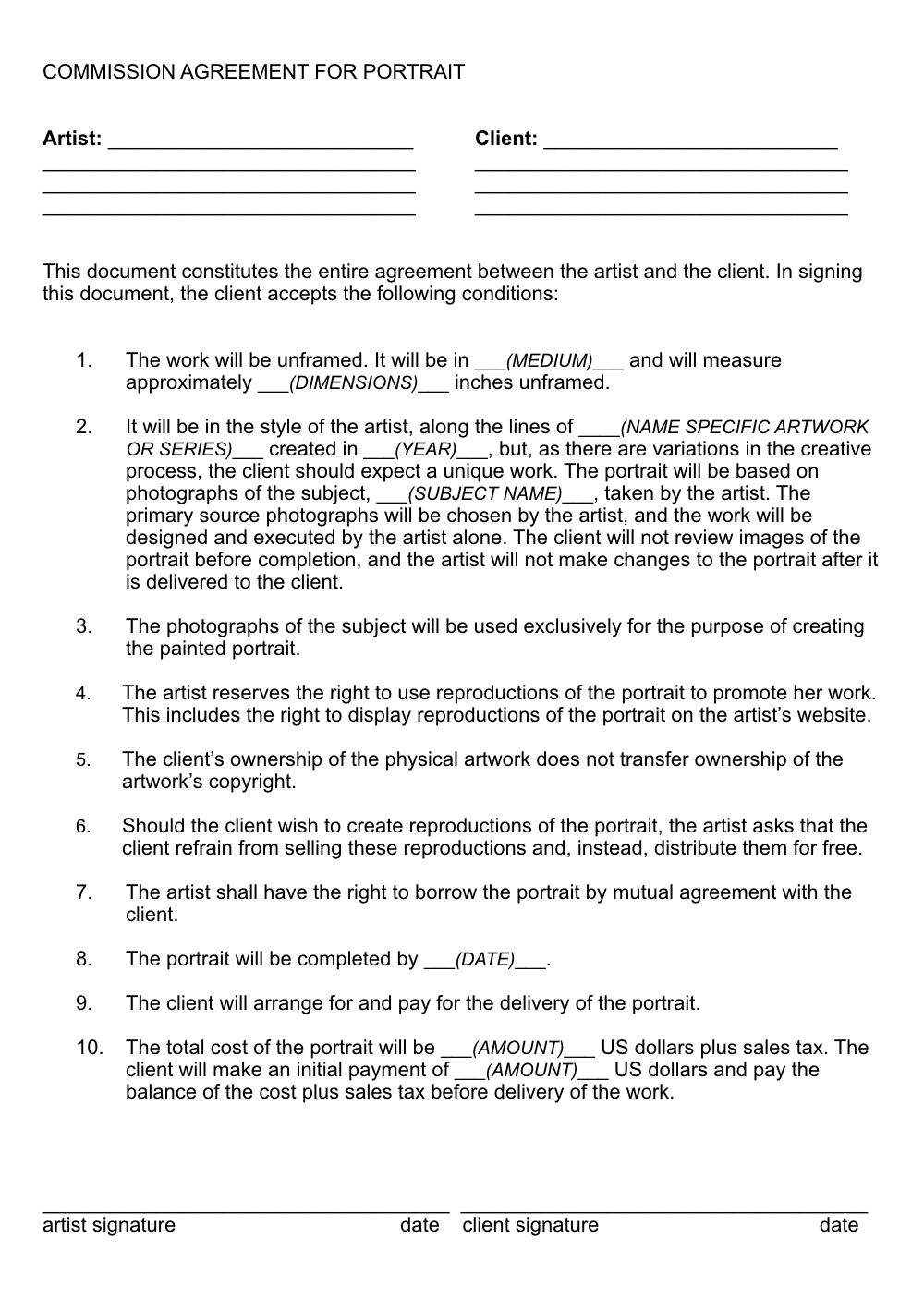

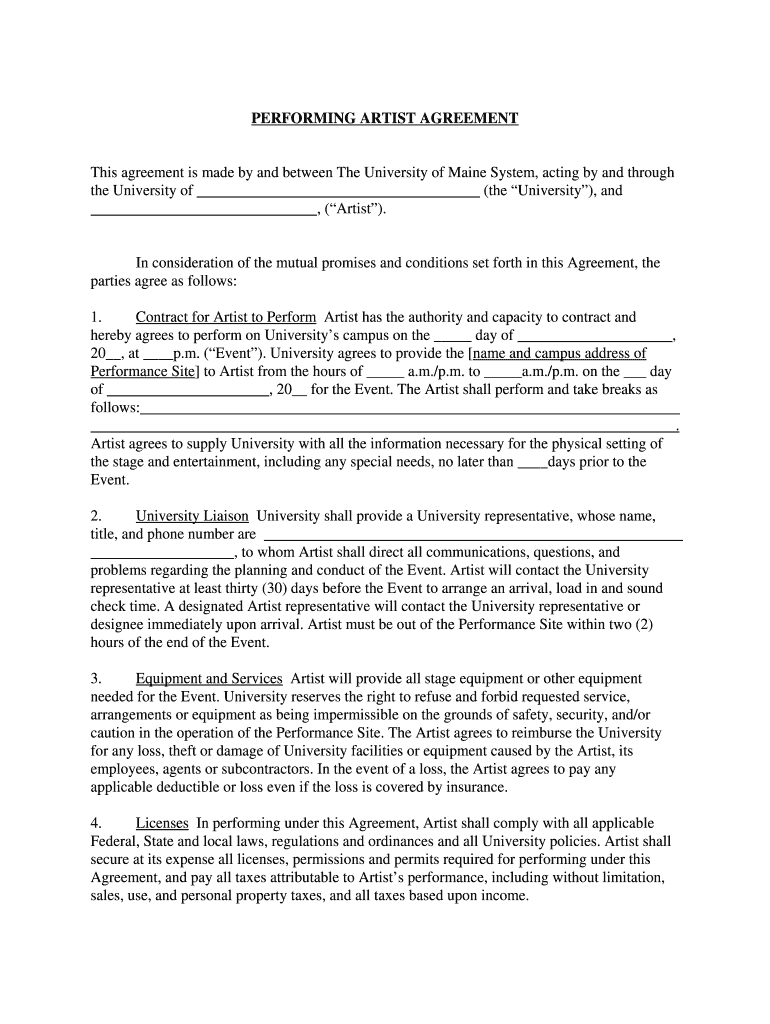

Simple Artist Contract Professional Practice Programmes

This has been a long and often painful process, which inevitably threatened the comfort zones of many who had come to rely upon these second and third generation documents. By the late 1980s, specialist art lawyers increasingly found themselves dealing with artlaw disputes arising out of naive or inappropriate uses of their original creations.During the 1990s, therefore, art lawyers began to introduce into professional practice programmes for art students, practitioners and administrators, new techniques and solutions to meet their contractual needs. Regrettably, these second and third generation documents came to be used as "quick fixes" by many artists and their clients, without giving them serious consideration. These contracts or agreements were intended by the specialist art lawyers who drafted them to serve either as examples of good practice or, more usually, to meet the unique contractual needs of a particular artist and client or commissioner.Pretty soon, however, certainly by the mid-1980s, there were in general circulation throughout the art world in the USA and the UK numerous adapted versions of what had been original bespoke documentation.

they are rather like borrowing someone else's shoes (they will have been worn-in by the original first owner whose feet may be the same basic size as the second-hand owner, but will not fit exactly and eventually damage their feet) they will have been originally created for a specific project, the requirements of which will not be the same as for any subsequent project Confusing PracticesSuch documents can be confusing both to artist and client because:

inter-personal negotiating skills. the essential ingredients of (in the case of public art commissions) what the artist and client need to do to make their project a success what it takes to achieve a legally enforceable and binding contract or agreement But what are good practices, and how can artists and their clients acquire them? Good PracticesA good practice tool kit should consist of three essential elements a basic understanding and sound working knowledge of: they are seen by artists (less often by commissioners) as being an easy, quick fix for aspects of professional practice which they would prefer (if possible) to ignore and therefore inhibit the artist from learning and developing from useful experiences of the commercial dimension.These are the key drawbacks of using such "off the shelf" contractual examples. they are often changed by the artist's and/or commissioner's attempting to customise them to meet their precise requirements and, by doing so, will usually undermine or degrade one or more key aspects of the original, so as to render it inappropriate (at best) or plain wrong (at worst)

That is a legally enforceable and binding contract if the newspaper is last week's edition, you are entitled to your money back (for breach of contract by the newsagent) or, if you did not give the correct purchase price by mistake, you must do so or return the newspaper (because you are in breach of contract with the newsagent). For example: you go to a newsagent to buy today's newspaper, saying which one you want and offering the asking price, take your purchase and any change. something which only qualified lawyers can create.These three points represent key myths about contracts which still exist in the minds of many artists and their clients.In the UK, legally enforceable and binding contracts are created and successfully executed by everyone, every minute of every day, without thinking we do not necessarily need lawyers or documents to do so, and most of us do not give them a second thought. a document agreed by the contracting parties and "signed, sealed and delivered"

And, on the whole, the system works well.In the case of artists and their clients, it is important at the outset of potential commercial discussions for both to appreciate that their conversations and behaviour may well result in a legally enforceable and binding deal being made (at least in the mind of the other party, if not also in their own mind) and for them to be absolutely clear what they intend, what has been agreed, and what has not.Good practice suggests that all discussions and eventual agreements on a project are committed to writing not to make the deal legally enforceable, but to avoid any confusion, misunderstanding, faulty memories, dishonourable changes of approach (and the like) and, if necessary, to assist any court to be satisfied that a deal was actually struck and what its terms were. Not so if necessary, the parties to the agreement could give evidence to the court about what they said and did, and so satisfy the court.This simple and flexible approach of UK law, developed over many centuries and now adopted in many other countries, is intended to facilitate the making of legally enforceable deals by ordinary folk, without the need for the involvement and cost of lawyers. At both these extremes, so long as the court is satisfied that there is "sufficient evidence" of the deal, then it will be recognised and given effect by the court.Myths and confusion often arise because many people still (wrongly) believe that if there is no documentary evidence of the deal, then there is no deal. In UK law, save in certain exceptional cases (such as transfer of ownership of freehold property or of intellectual property rights), an agreement will be legally enforceable and binding if there is sufficient evidence that a commercial offer was actually made and accepted.The important phrase in the previous sentence is "sufficient evidence" which, in its simplest form, could be the evidence given in court by the disputing parties that a deal was done and what its terms were at its most complex, such evidence could take the form of a written agreement, drawn up by qualified lawyers for both parties, and signed in the presence of witnesses. How so?UK law has for centuries allowed people to make legally enforceable and binding bargains/deals in their own ways, without dictating how they should do so unlike in some foreign countries where commercial contracts are often governed by a strict mercantile (or commercial) legal code specifying that such contracts must be made in writing, signed by the parties, and/or witnessed or drawn up by a qualified lawyer. The buyer is in breach of contract, and still owes you the agreed purchase price.In both these examples, the most important point is not simply that there were breaches of contract, but the fact that in each case a legally enforceable binding contract had actually been made.

What can be done is to offer a basic structure of the essential ingredients upon which the contracting parties should always negotiate and agree (or disagree).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)